Iron deficiency anaemia and atrophic gastritis – unravelling the loop

Defining criteria

WHO guidelines define anaemia as a haemoglobin (Hb) concentration below 130 g/l in men over 15 years of age, below 120 g/l in non-pregnant women over 15 years of age, and below 110 g/l in pregnant women in the second or third trimester.1

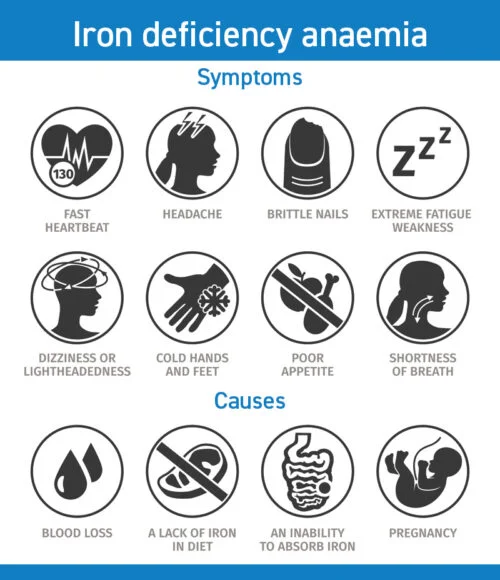

IDA results from an insufficient reserve of iron in the body, which causes a net reduction in the production of red blood cells.

Iron is also pivotal for many other metabolic processes too and so deficiency is considered a global healthcare priority, not only because of its high prevalence – in 2-5 % of adult men and post-menopausal women1 – but also because of its sequels and significant impact on quality of life. The cause is often multifactorial and IDA itself is not considered a disease, more a consequence of disease.

It commonly presents across all tiers of healthcare and, in some cases, IDA may require urgent non-elective investigation and lengthy hospital stays. IDA is estimated to cost the NHS more than £90m per year2 and this figure is likely to continue increasing, so identification of the cause and successful treatment of IDA at an early stage is key to positive outcomes, as well as to reducing economic burden.

Investigations of IDA include a variety of haematologic, endoscopic and radiologic tests, often combined with oral or intravenous iron replacement therapy to treat the condition and evaluate response to therapy. Haematologic diagnosis of IDA is often made by performing full blood counts, iron studies and determining serum ferritin levels, which give an indication of the body’s store of iron. If the serum ferritin is less than 30 μg/l, this is considered sufficient to confirm the diagnosis of iron deficiency. However, there are a number of conditions that affect the reliability of serum ferritin levels. For example, in the case of infection or inflammation, IDA can be masked by high ferritin levels and, in pregnancy, ferritin levels may be less reliable.

IDA – there’s often a gastrointestinal connection

IDA should be diagnosed swiftly and it is very important to identify the cause because it is often secondary to an underlying condition. Fast identification and treatment of the cause of IDA as part of patient investigations is essential to determine whether the condition is caused by dietary insufficiency, malabsorption, or loss of iron, because the cause will determine the treatment plan, and often its success. In the case of malabsorption or loss, IDA can be a consequence of GI pathologies and, in fact, according to the British Society of Gastroenterology1, this can be the case in as many as one third of men and post-menopausal women.

Chronic GI conditions, such as atrophic gastritis, coeliac disease, active inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), and enteropathy, all predispose to iron malabsorption. The same applies when gastric surgery has taken place. Iron can be rapidly depleted through menstrual loss too, as well as through blood loss in GI diseases such as IBD and cancer. In the UK, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) referral guidelines for suspected lower GI cancer suggest that IDA with Hb concentrations of less than 110 g/l in men or less than 100 g/l in non-menstruating women warrant fast-track referral.3

Atrophic gastritis, achlorhydria and IDA – what do we know about this relationship?

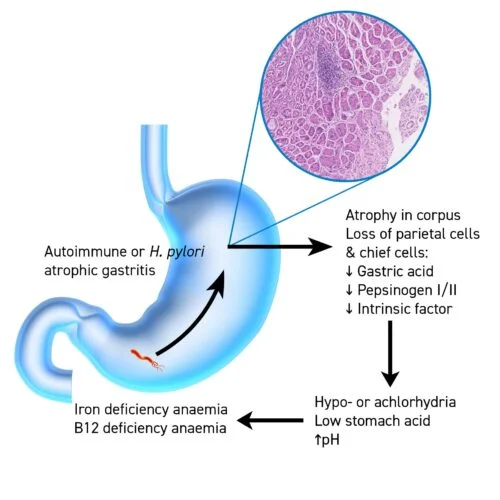

Where IDA is suspected and confirmed by haematologic investigations, but there are no obvious clinical signs for its cause, the next step in the care pathway includes a ‘top-and-tail’ endoscopic examination, that is, a gastroscopy and colonoscopy – often performed in one session – to investigate the cause. Gastroscopy and targeted gastric mucosal biopsies can help identify one of the more ‘hidden’ precursors to IDA – a chronic condition called atrophic gastritis (AG). AG is often symptomless as far as gastrointestinal symptoms are concerned but, importantly, is characterised by the loss of gastric cells and therefore leads to an impaired secretion of gastric acid in the stomach. Gastric acid plays a vital role in plasma iron homeostasis as the low pH helps to regulate the optimal environment in the proximal duodenum for the conversion of the insoluble ferric form of dietary iron (Fe3+) to the absorbable ferrous form (Fe2+). When chronic AG has caused hypochlorhydria (reduced gastric acid) or achlorhydria (no gastric acid), iron malabsorption is one of the consequences.

For many decades, researchers have been trying to understand whether achlorhydria precedes IDA, or if it is the other way round. Recently, correlational data from four longitudinal studies corroborated that gastritis can be the causal factor for IDA, due to impairment of nutrient absorption. Iron malabsorption manifesting as IDA, vitamin B12 deficiency, in particular, leads to pernicious anaemia and reduced bone mineral density or vitamin D and calcium deficiency causing osteoporosis and bone fracture.4

Available research has also shown that the frequency of achlorhydria is 44 % in patients with idiopathic IDA, compared to 1.8 % in healthy controls, and there is no evidence suggesting that iron deficiency can lead to achlorhydria.5

A stamp of approval for GastroPanel®

A stamp of approval for GastroPanel®

IDA is an extremely complex condition requiring the expert input from several disciplines to identify, diagnose, investigate and treat it. Where the gastrointestinal tract is involved, new initiatives have been recommended to evaluate how non-invasive diagnostic tests can help yield meaningful results when investigating adult patients newly diagnosed with IDA. The British Society of Gastroenterology has recently updated its guidelines for IDA management in adults and recommends further research into the use of comprehensive tests such as BIOHIT’s GastroPanel1, which could aid the investigation of IDA by screening for AG and achlorhydria. GastroPanel looks at three separate biomarkers, in combination with a test for Helicobacter pylori non-invasively from a single blood sample, to detect AG and achlorhydria:

- Pepsinogen I;

- Pepsinogen II;

- Gastrin-17;

to help identify at risk patients for early intervention. GastroPanel also includes a test for Helicobacter pylori, the dominant cause of AG which could help direct concomitant treatment strategies that include H. pylori eradication therapy. As a chronic disease, H. pylori may have been harbouring in the stomach of some IDA patients for many years exerting its pathological effect and causing damage to the gastric mucosa.

The treatment perspective

Although there is no specific cure for achlorhydria, it is important to identify whether AG is the cause of IDA, not only to enable the most appropriate strategy for iron replacement therapy to be selected, but also because AG is a significant risk factor for gastric cancer. When AG is identified it is recommended that patients undergo endoscopic surveillance of the condition so that the risk of disease progression can be monitored closely.6 Patients diagnosed with AG may benefit from intravenous iron replacement therapy because it does not rely on gastrointestinal integrity, and although intravenous therapy is considered to be a more expensive therapeutic option than oral therapies, it may be tolerated better with greater efficacy and ultimately reduce the overall cost burden of untreated iron deficiency and IDA related emergency admissions.

The bottom line

Where gastrointestinal investigation is warranted in the investigation of IDA, straight-to-endoscopy strategies incur high costs, relatively low yield, and health service pressures. By introducing non-invasive serological testing for pepsinogens before gastroscopy, referrals and gastric biopsies may deliver more robust diagnostic results for GI conditions like AG, H.pylori infection and achlorhydria, in the investigation of the cause of IDA. GastroPanel is a non-invasive, risk-free and user-friendly blood test panel that provides information on damage to the gastric mucosa or atrophy to the gastric glands, and indirectly helps to cement a diagnosis of achlorhydria-driven IDA.

To find out more about BIOHIT’s GastroPanel, visit www.biohithealthcare.co.uk/gastropanel.

References

- Snook J, Bhala N, Beales ILP, et al. British Society of Gastroenterology guidelines for the management of iron deficiency anaemia in adults. 2021 Nov;70(11):2030-2051

- Brookes MJ, Farr A, Phillips C, et al. Management of iron deficiency anaemia in secondary care across England between 2012 and 2018: a real-world analysis of Hospital Episode StatisticsFrontline Gastroenterology 2021;12:363–369.

- NICE guideline. Suspected cancer: recognition and referral. Published: 23 June 2015 www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng12

- Clements, M., Hoey, L., Ward, M., Hughes, C., Porter, K., Cunningham, C., McNulty, H. (2021). Impact of atrophic gastritis on vitamin B12 biomarkers and bone mineral density in older adults from the TUDA study. Proceedings of the Nutrition Society,80(OCE1), E44. doi:10.1017/S0029665121000458

- Betesh AL, Santa Ana CA, Cole JA, Fordtran JS. Is achlorhydria a cause of iron deficiency anemia? Am J Clin Nutr. 2015 Jul;102(1):9-19. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.114.097394. Epub 2015 May 20. PMID: 25994564

- Pimentel‐Nunes P, Libânio D, Marcos‐Pinto R, et al. Management of epithelial precancerous conditions and lesions in the stomach (MAPS II): European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE), European Helicobacter and Microbiota Study Group (EHMSG), European Society of Pathology (ESP), and Sociedade Portuguesa de Endoscopia Digestiva (SPED) guideline update 2019. Endoscopy. 2019 ; 50 : 456 ‐ 457